We took advantage of the beautiful weather this past weekend and went for a walk through East Boston’s Eagle Hill neighborhood.

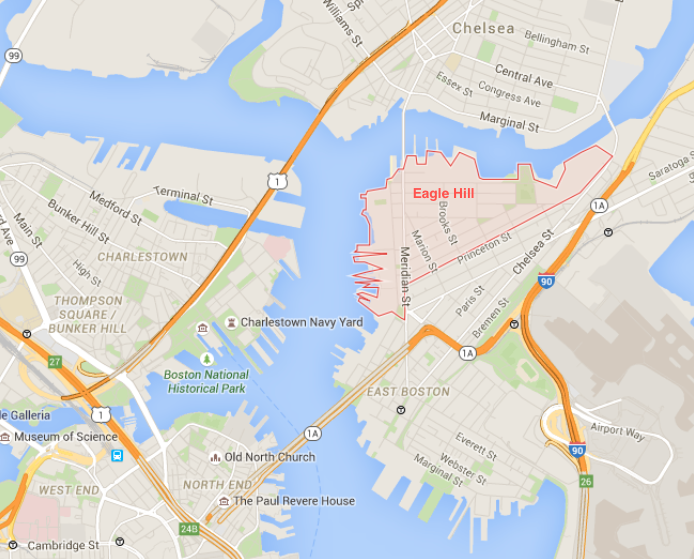

Eagle Hill is a quiet, mostly residential neighborhood tucked into the northwest corner of East Boston, directly across the harbor from Charlestown, another of Boston’s harbor-front neighborhoods. Eagle Hill’s dense collection of wood-frame, Victorian houses, hilly terrain, and proximity to the waterfront – not to mention the large number of excellent Mexican and Central American restaurants around the neighborhood – remind me a little of San Francisco. It’s an architecturally unique area within Boston, and a large swath of the neighborhood near the top of the hill has been designated a historic district under the National Register of Historic Places.

We took a meandering route, beginning at Bremen Street Park, a long strip of green space next to a raised highway that was reclaimed from an airport parking lot in 2007. Leaving the park behind, we slowly zig-zagged our way up the Hill, wandering down a street and then moving up a block and walking back the way we had come. Eagle Hill is laid out in a grid, with east/west streets named for Revolutionary War battles (Saratoga, Lexington, Trenton) and north/south streets named for Revolutionary War generals (Marion, Brooks, Putnam). This naming system, put in place in the 1830s, seems appropriate, given that the second battle of the Revolutionary War was fought on and around Eagle Hill back when the area was pastureland. American forces sunk a British schooner just off the coast of Eagle Hill in the first naval engagement of the war. Aside from the street names, nothing remains to commemorate the battle, although this Memorial Day, a community canoe and kayak regatta will retrace part of the battleground along the East Boston shoreline.

Whenever I visit Eagle Hill, I find myself admiring the neighborhood’s architecture. As we walked, we passed block after block of late-19th century houses, many with immaculately restored facades. At the foot of the Hill, we walked along a full block of mansard-roofed, brick row houses built in the 1860s.

Eagle Hill was divided into residential parcels and sold for development beginning in the 1830s. The original developers envisioned the area as a high-end suburb, perched atop a hill, separated from downtown by the harbor, and filled with spacious estates owned by some of Boston’s wealthiest residents. A number of these single-family, suburban mansions were actually built and several, like these two located near the top of the Hill, survive to this day.

By the mid-1800s, East Boston, with its expansive waterfront along Boston’s inner harbor, had become a center of the shipbuilding industry in New England. During the 1850s, some of the fastest clipper ships in the world were built here. The Flying Cloud, one of the most famous clipper ships of its time, was built by Donald McKay at his East Boston shipyard, and in 1853 set the sailing record for the “Golden Route” from New York to San Francisco around Cape Horn, covering over 16,000 miles in 89 days. The record stood for over 130 years until it was broken in 1984. There are a number of plaques and murals in East Boston’s parks that celebrate the neighborhood’s maritime history, including this mural along the East Boston Greenway.

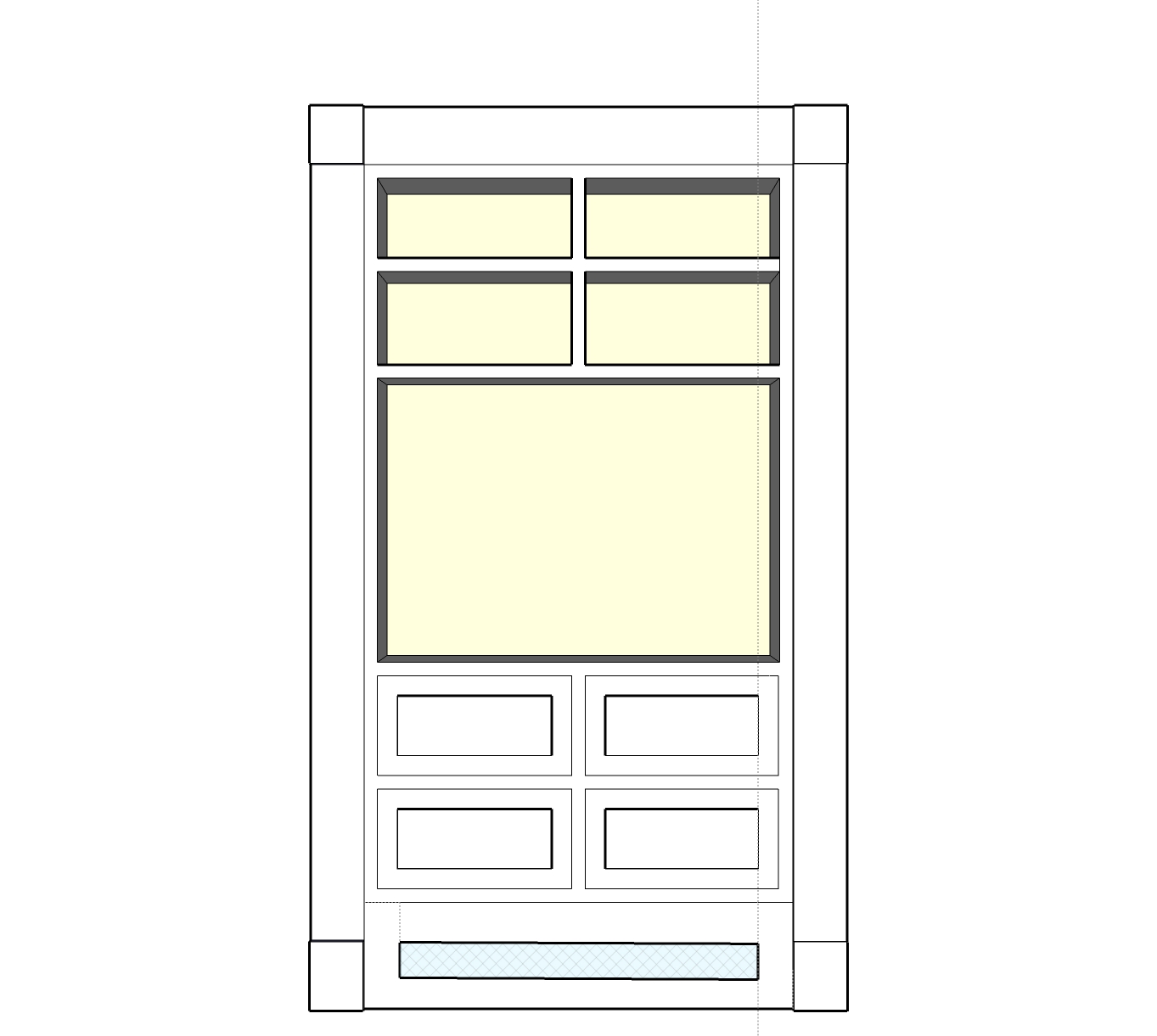

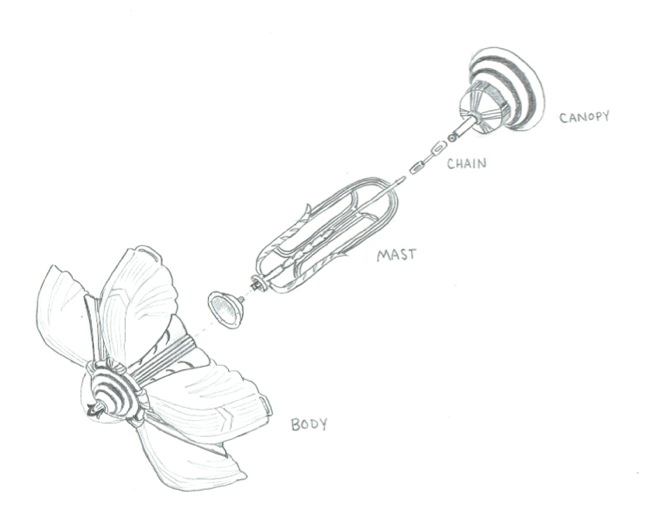

East Boston’s shipbuilding industry expanded rapidly during the California Gold Rush, as demand increased for quick transportation to and from the west coast. As shipyards along the waterfront grew, they attracted carpenters, sail makers, and other shipbuilding artisans to the area, many of whom hailed from the Canadian Maritime Provinces. Most of Eagle Hill’s current housing stock was built between 1850 and 1890 to house this influx of middle-class workers. Many of the shipbuilders who constructed their homes on Eagle Hill viewed their private residences as advertisements for their work, and so a bunch of especially fancy homes were built here during the clipper ship era. Houses dating from this time were almost exclusively built in the Italianate and Second Empire styles popular in the late 1800s (think lots of mansard roofs and paneled window bays). Despite the original developers’ hopes for a wealthy, suburban neighborhood, Eagle Hill began to take on its present urban character during this time. Two and three story end houses, with the short, gabled end of the house facing the street, were built one after the next on long, narrow lots.

As we continued up the Hill, we passed Angela’s Cafe, one of the best Mexican restaurants in Boston. We were tempted to stop in for a snack, but the line for a table was out the door, so we moved on. The wide array of Latin American restaurants and corner stores in and around Eagle Hill is a reflection of the neighborhood’s large Central and South American immigrant community. In part because East Boston has a long history as a transportation hub, it has been home to a large immigrant population for well over 100 years. Irish, Italian, and Jewish immigrants arrived in East Boston beginning in the late 19th century, and as demand for housing increased in the early 20th century, many of Eagle Hill’s formerly single family homes were divided into apartments. Mansard roofs on some houses were squared off to make room for a full top floor apartment, and many houses in the neighborhood were modified to more closely resemble triple deckers, the three story apartment buildings that were being built in other working class Boston neighborhoods at the time.

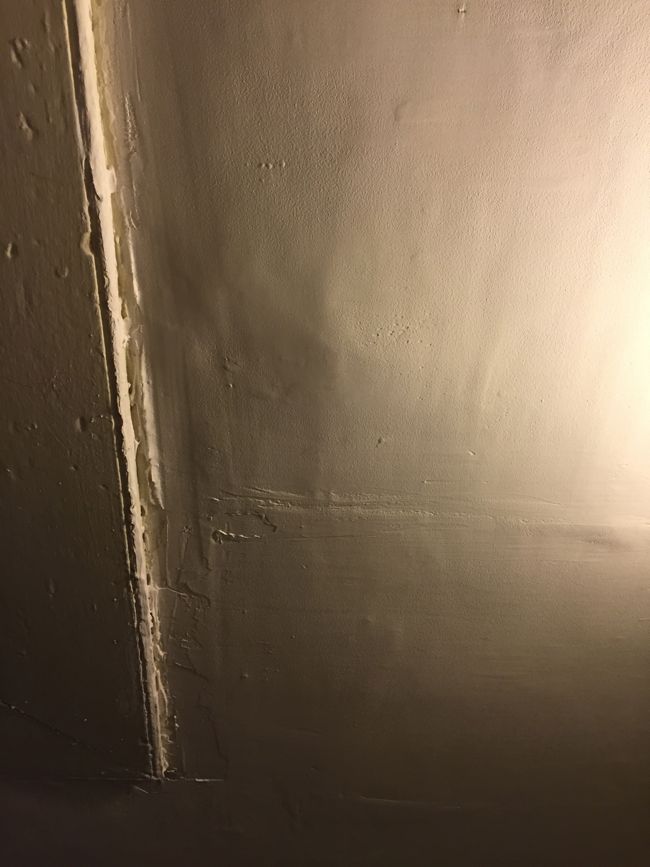

Over the course of the 20th century, a lot of Eagle Hill’s 19th century architecture was heavily modified. External ornamentation was removed and houses were re-sided in vinyl and cedar shingles. Original slate roofs were replaced with asphalt shingles and copper gutters were traded for aluminum. Most of these modifications were made in the name of modernization and convenience before the value of the Victorian architecture had been fully recognized. But in the late 1980s, a group of Eagle Hill residents formed the Eagle Hill Civic Association to advocate for restoration and preservation of the neighborhood’s historic architecture. Their efforts led to the designation of the neighborhood as a National Register of Historic Places historic district in 1998. During the past 25 years, many Eagle Hill homeowners have restored their houses’ historic facades. And even as we walked around the neighborhood last weekend, we saw a lot of ongoing renovation and restoration projects.

A restoration project had just begun on the teal house on the right in the picture below. The vinyl siding was removed around the lower window bay, exposing the original wood paneling.

As we reached the top of the Hill, we came across one of the neighborhood’s largest collections of fully restored houses surrounding Putnam Square. Putnam Square is really more of a triangle where three streets intersect with a small park and a fountain at its center. On a nice day, it’s a great spot to sit on a bench and relax for a bit.

Some of my favorite houses in Eagle Hill are little, two-story, mansard-roofed cottages. There’s a bunch of them scattered around the neighborhood, but I haven’t come across this kind of house anywhere else. I like the way that such a grand architectural style was imposed on a modestly-sized house. Most of these cottages seem to have been too small to convert into apartments and so remain single family homes today. If I were ever to buy a single family house, I think one of these with a nice back yard would be ideal.

After wandering through Putnam Square, we walked down the back side of the Hill to the Condor Street Urban Wild, a former industrial site along Chelsea Creek that underwent hazardous waste cleanup and ecological restoration in 2003. The site is now a mixture of natural coastal habitat, including a salt marsh, mud flat, and meadow. It offers a tiny glimpse of what Eagle Hill may have looked like hundreds of years ago, before it was settled.

Today, Eagle Hill, along with the rest of East Boston, remains one of Boston’s more economically and culturally diverse neighborhoods. But signs of gentrification have begun to appear within the past few years. Rents and property values, although still affordable by Boston standards, are on the rise, and overeager real estate agents have begun comparing East Boston to Brooklyn. Community improvements, including a new library branch, and new parks, playgrounds, and athletic fields have popped up all over the neighborhood. East Boston has a long history of welcoming newcomers to the city, whether young professionals or recent immigrants. The neighborhood also has a strong tradition of community activism – residents fought the encroachment of Logan Airport and advocated for more green space for decades, and, more recently, blocked a proposed casino. So East Boston seems well positioned to deal with the challenge of ensuring that the neighborhood remains welcoming, affordable, and desirable for all residents.

Eagle Hill is an often overlooked neighborhood. There are even people who have lived in Boston for years who have never heard of it. So if you find yourself in Boston and are looking for a historic, off-the-beaten-path neighborhood to explore, jump on a blue line train, head across the harbor, and check out Eagle Hill.