This post is part of a series about the process of nominating my neighborhood for the National Register of Historic Places. To see all of the posts in the series, click here.

Although not usually considered part of the Jeffries Point neighborhood, Maverick Square, located a five minute walk to the west, is the closest major business district. If you take a Blue Line train from downtown Boston, Maverick Square is the first subway stop you’ll reach in East Boston, so it’s often the first part of East Boston that new visitors to the neighborhood experience. It’s the oldest section of East Boston, and, historically, it’s served as the economic and civic heart of the neighborhood. Let’s take a look at how Maverick Square has changed over the past century or so in a series of three Then and Now photos. Use the slider in the center of each image to compare past and present.

See here and here for more Then and Now photos of Jeffries Point.

Maverick Square

Left: 2017 | Right: 1890s

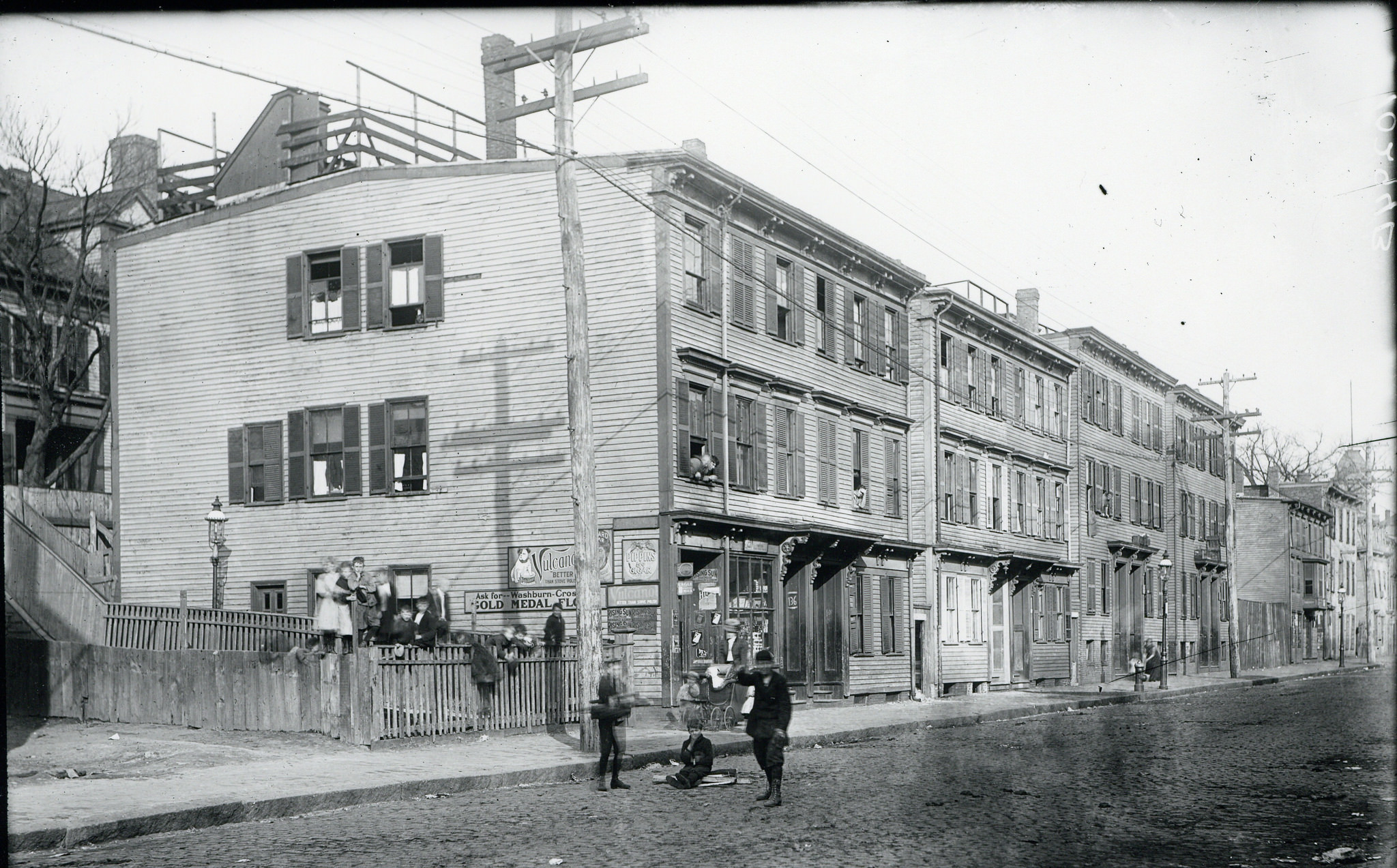

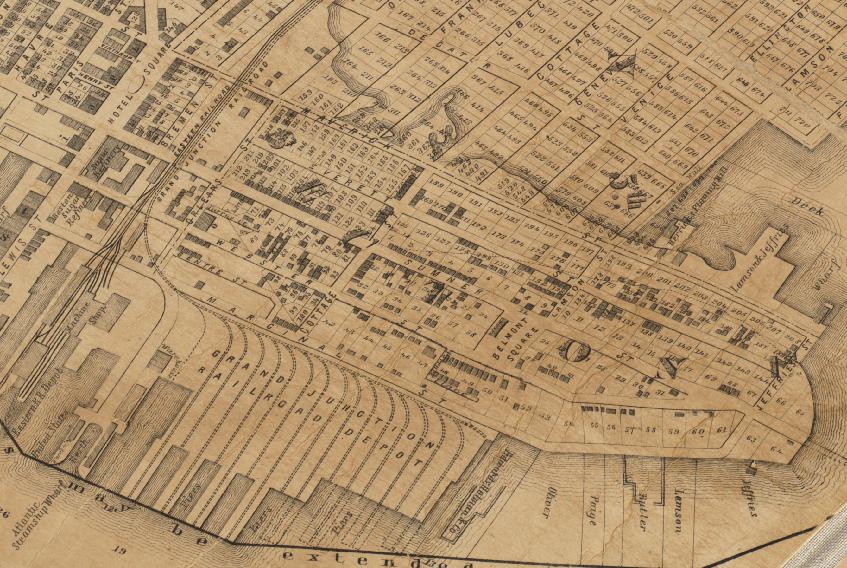

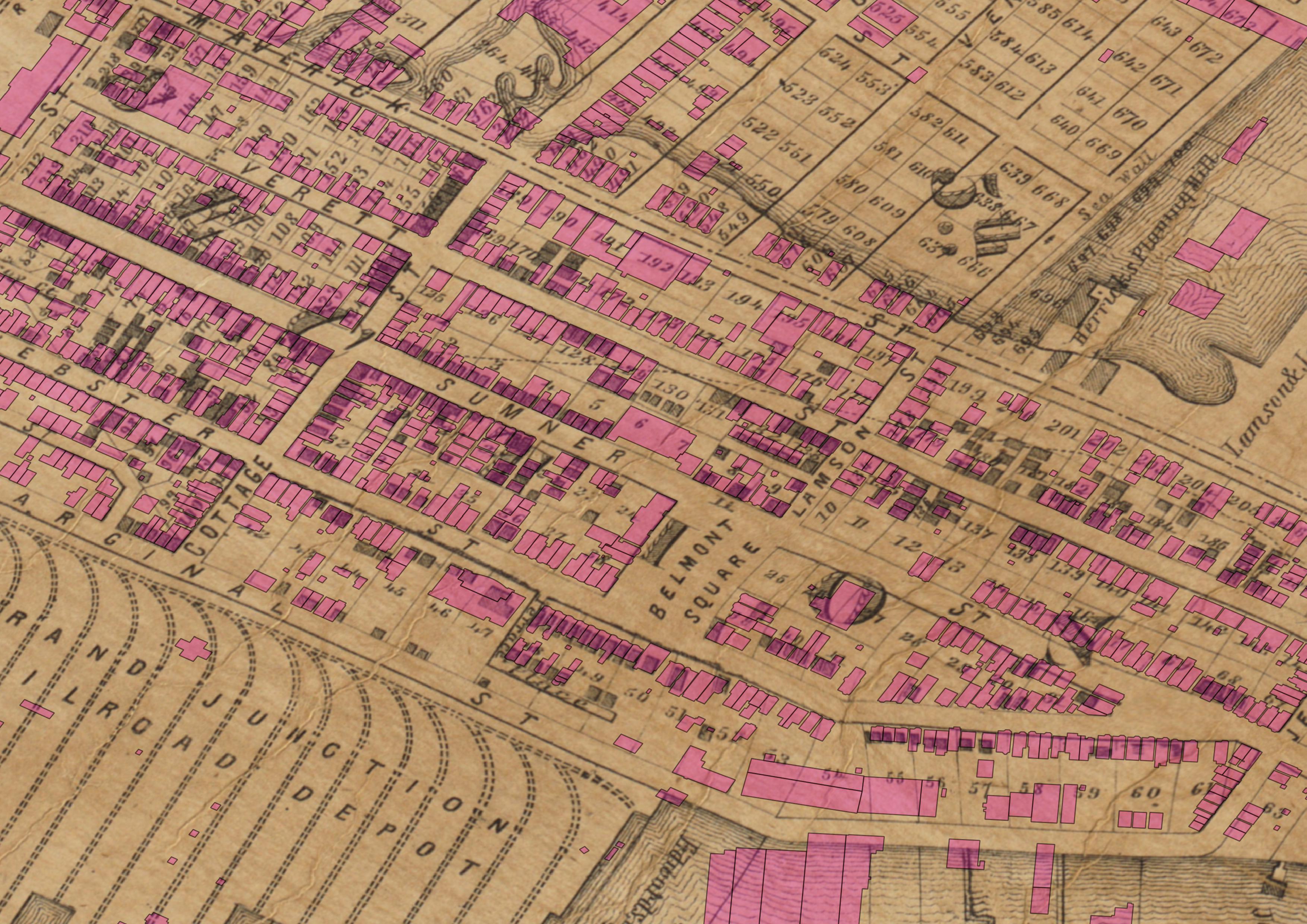

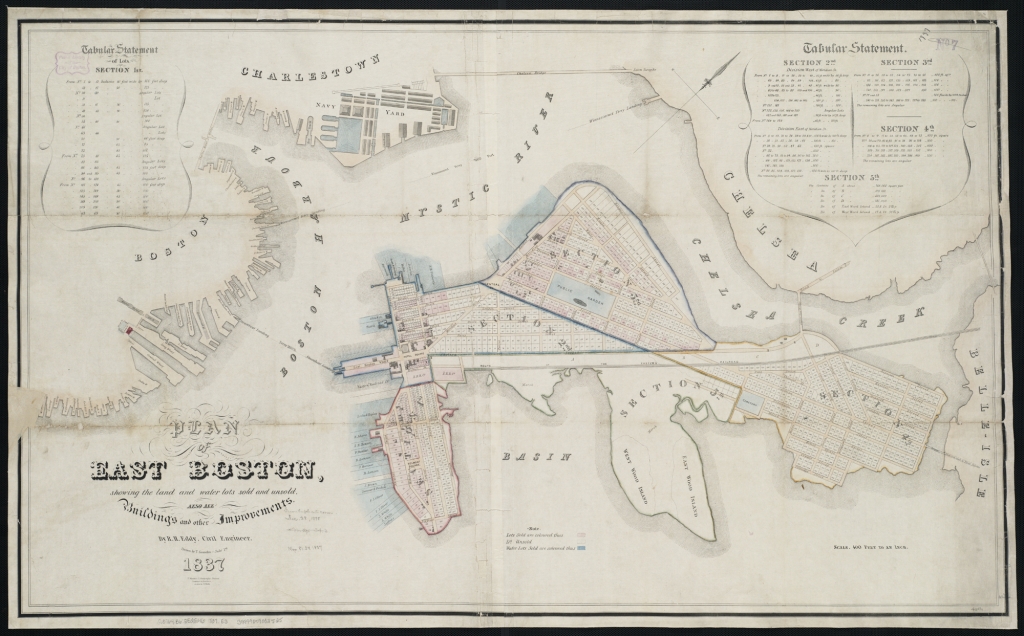

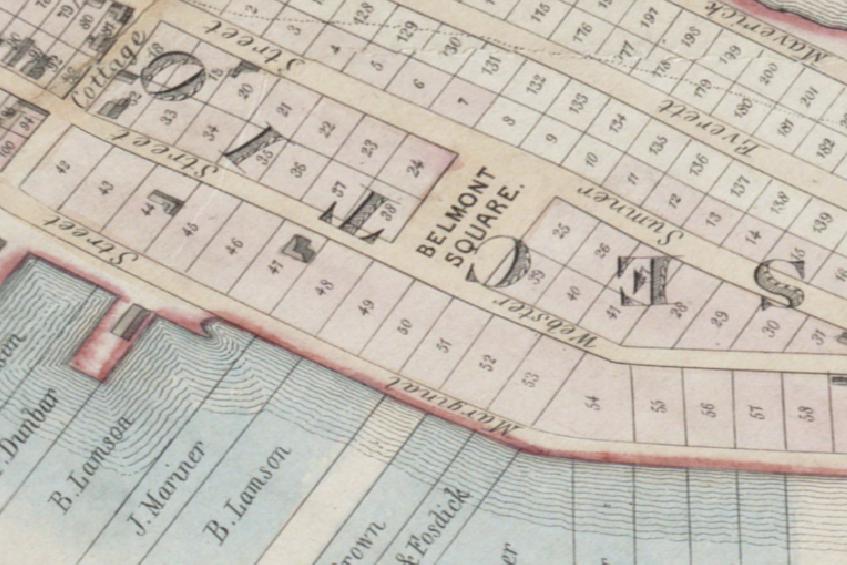

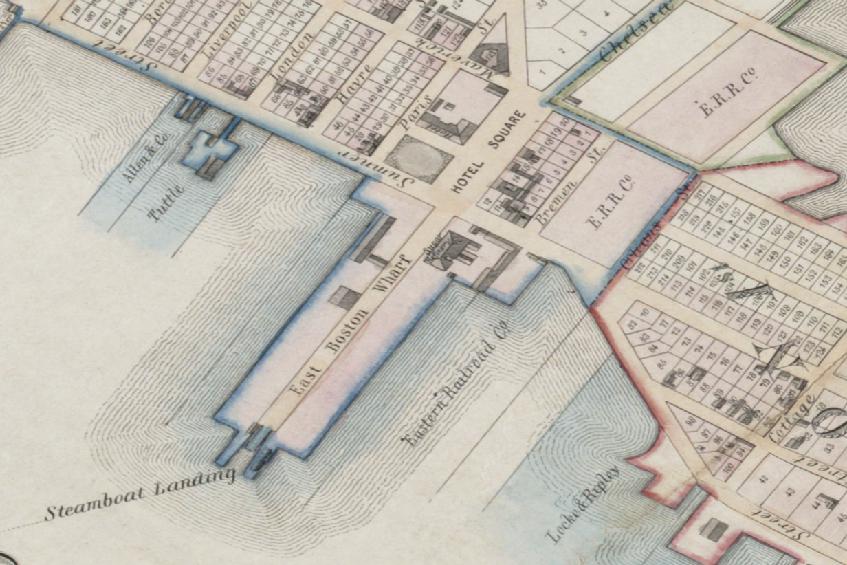

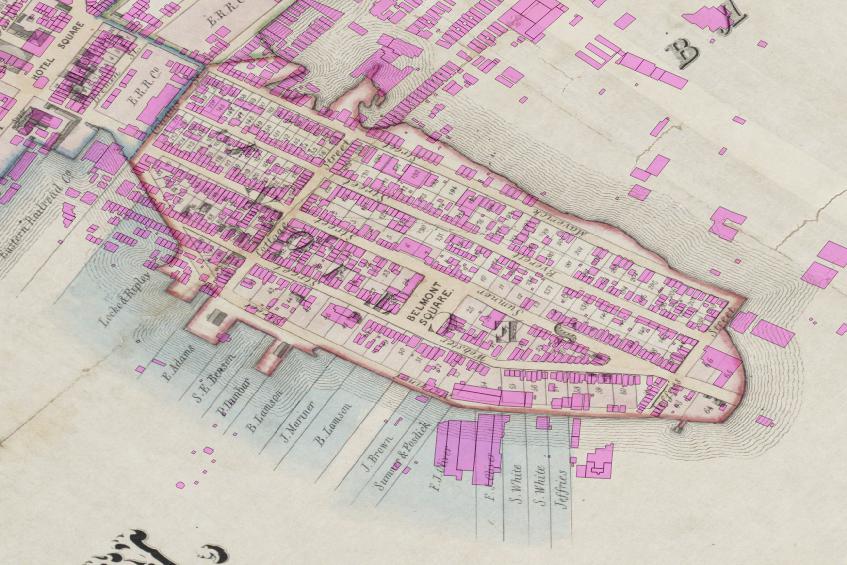

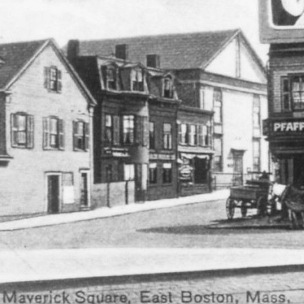

Located just to the west of Jeffries Point, Maverick Square was the site of the earliest development in East Boston starting in 1833. By the mid-19th century, Maverick had become a busy shopping district. An oval-shaped, landscaped green space at the center of the square was surrounded by clothing stores, pharmacies, groceries, cigar shops, and a furniture store. The Boston Sugar Refinery, constructed in 1836 and famous for its invention of granulated sugar, towered over the southern end of the Square. (It’s the large, gable-roofed building at the back left of the 1890s photo.)

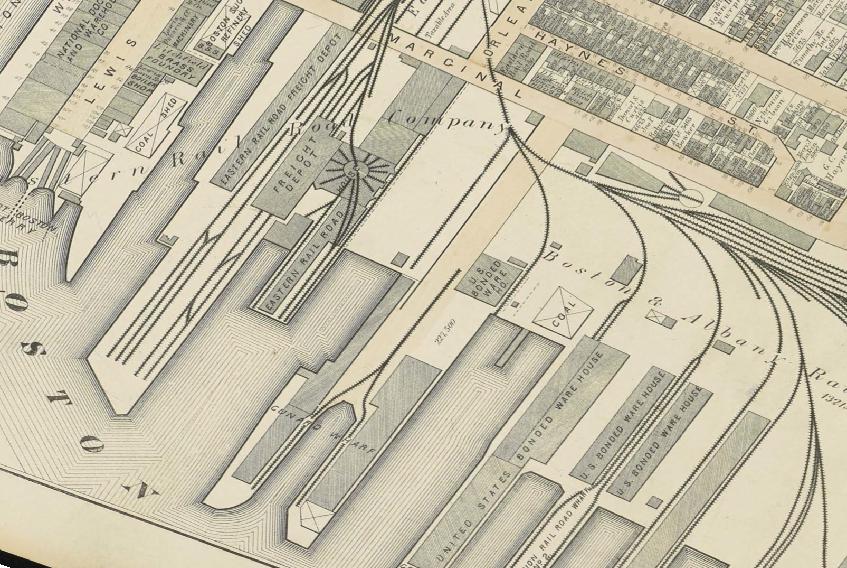

But Maverick Square was more than a commercial district, it was also the civic heart of the neighborhood, home to a Congregational Church, the offices of the local newspaper, Lyceum Hall – a public venue that hosted lectures, debates, and entertainment events – and the East Boston Savings Bank – a locally-owned bank that provided capital to local businesses (and which still exists today). The Square was also a transportation hub. The original ferry landing that connected the island neighborhood to mainland Boston was located at the southern end of Maverick Square. European immigrants and visitors arrived at the Cunard Steamship Terminal along the waterfront just to the east of the Square, and travelers from as far away as Albany, NY arrived at the Eastern Railway Terminal at the northern end of the Square. The five-story tall Sturtevant House Hotel, commonly called the Maverick House (the name of two hotels that previously occupied the same site between 1833 and 1856) dominated the western side of the Square and provided lodging for the thousands of travelers that passed through the area. At the time, it was the largest building on the Square, visible on the right side of the 1890s photo.

All of this changed during the 20th century as East Boston entered a period of population decline. One by one, Maverick Square’s grand, 19th century buildings came down. The Sturtevant House Hotel: demolished, 1927. Lyceum Hall: lost to fire in the 1940s. The upper floors of the Winthrop Commercial Block: demolished by the middle of the 20th century, leaving behind a squat, one-story structure. The Boston Sugar Refinery, Maverick Congregational Church, the original East Boston Savings Bank building, all were lost by the end of the 20th century. The grand, urban square of the 19th century had largely disappeared, replaced by a hollowed out, gap-toothed streetscape.

Interestingly, as buildings disappeared from Maverick Square, new skyscrapers popped up across the harbor, a sign of Boston’s economic retreat from its inner neighborhoods and reinvestment in the downtown financial district during the 20th century. The downtown skyline, visible today across the harbor behind Maverick Square, did not exist at the turn of the last century.

Today, some of the gaps in Maverick Square’s streetscape are beginning to be filled in. A new neighborhood health center building, approximately the same size and shape as the old Sturtevant House Hotel that once occupied the site, was completed a few years ago.

East Side of Maverick Square

Left: 2017 | Right: ca. 1900

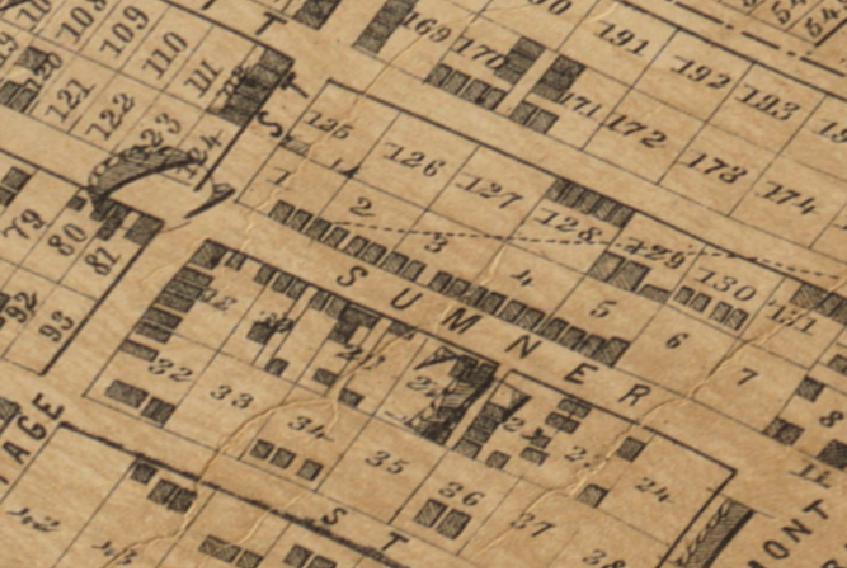

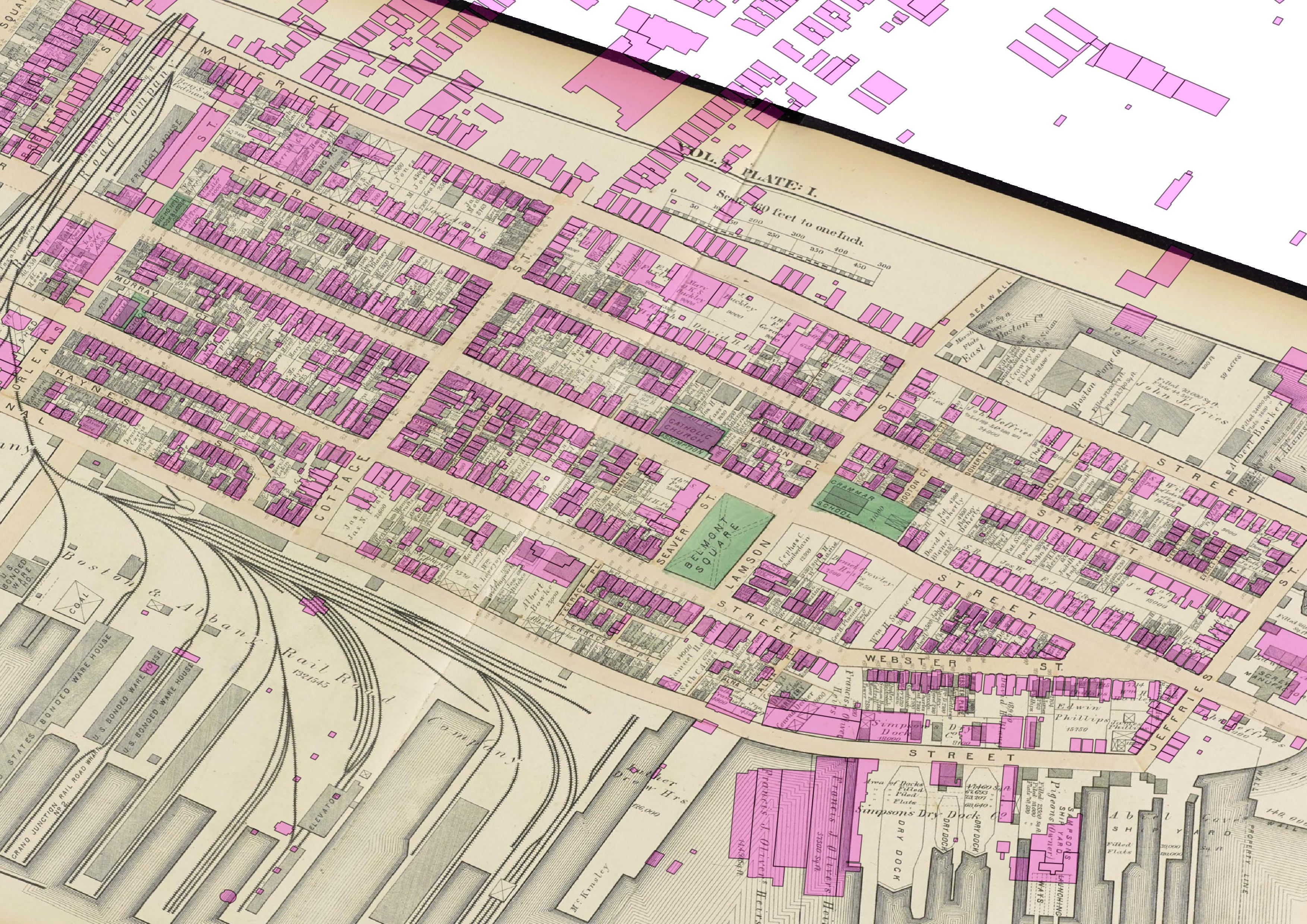

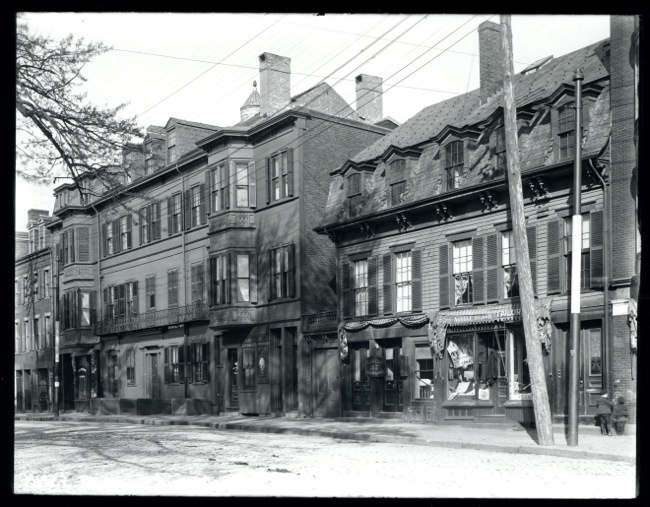

The photo above shows the southeastern side of Maverick Square around 1900 and again today. This side of the Square features the highest concentration of surviving 19th century buildings in the immediate area. Most of the buildings seen here were built at the tail end of the 19th century, although many of them have been significantly altered over the years. You can just make out tree branches at the top of the ca. 1900 photo, hinting at the landscaped green space that once occupied the center of the square. This central green space was destroyed in 1904 during the construction of a subway tunnel running from Maverick Square under the harbor to downtown Boston. When it was built, it was the longest underwater tunnel in the world, and it’s still in use today, carrying Blue Line trains to and from downtown. Today, the center of Maverick Square has been given over to pavement and parking spaces.

144-146 Maverick Street

Left: 2017 | Right: ca. 1900

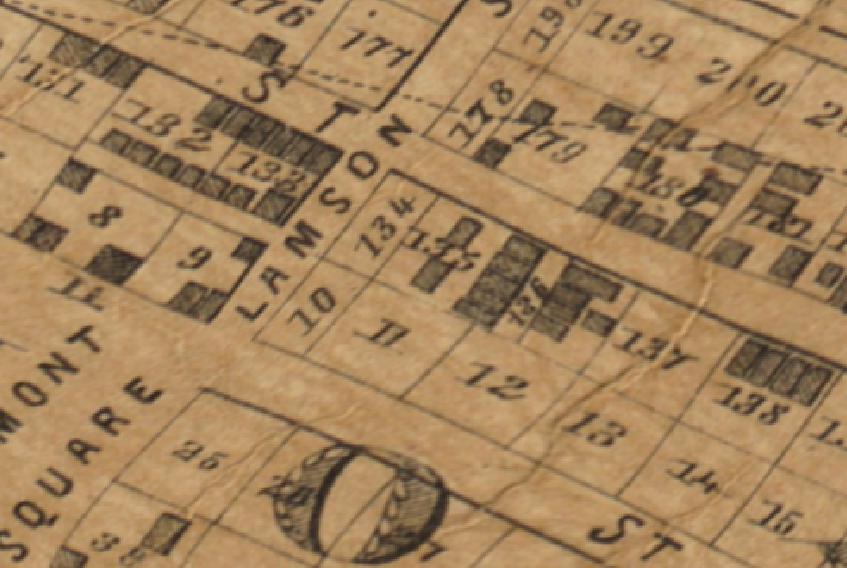

The pair of brick townhouses seen here at the center of the photo are some of the last 19th century buildings remaining at the northeast corner of Maverick Square. These handsome houses were built in 1870 by a local mason who lived at the opposite end of the Square. At the time, East Boston’s wooden shipbuilding industry was failing, and the neighborhood was entering a period of economic stagnation and slowed growth as shipyard workers moved away. Given this uncertain economic climate, the construction of these stylish, upper-middle class homes was an act of wild optimism. The local builder was doubling down on his neighborhood, risking his own money in defiance of a disintegrating local economy. It was almost as if he believed that constructing substantial and beautiful housing in Maverick Square would somehow usher in a return to the prosperity and growth that had defined East Boston’s early years.

Unsurprisingly, the townhouses were not as successful as the builder must have hoped. As upper-middle class, single family homes, they were failures almost as soon as they were built. Within a decade the townhouses were converted to boarding houses, providing immigrant newcomers and working people with a stylish, affordable place to live. In the 1940s, the ground floors of the townhouses were converted to retail space. Even though they may have never been used for their intended purpose as single family homes, the townhouses at 144-146 Maverick have somehow survived intact, against all odds, for nearly 150 years, serving the needs of a changing community, providing adaptable residential, retail, and office space.

Until now. These townhouses were purchased by developer Linear Retail last year and are slated for demolition to make way for a generic, two-story retail building. The destruction of these buildings, some of the oldest and best preserved buildings remaining in Maverick Square, would be a terrible loss for the community. An informal group of East Boston residents, myself included, have banded together in a last ditch effort to save the townhouses. Through our efforts, the Boston Landmarks Commission has listed the townhouses as pending Boston Landmarks, but the future of these buildings remains uncertain.