This post is part of a series about the process of nominating my neighborhood for the National Register of Historic Places. To see all of the posts in the series, click here.

The Greek Revival style dominated American buildings for nearly 40 years. In the 1840s and 50s, hundreds of Greek Revival houses were built across the Jeffries Point neighborhood to accommodate East Boston’s growing population. But after the Civil War, the style fell out of fashion. The national mood had shifted. Greek Revival architecture, once considered a stately expression of civic pride, suddenly seemed stuffy, overly serious, and old-fashioned, a painful reminder of the country’s antebellum past.

After the trauma of the Civil War, Americans were ready for something new. They began choosing more and more elaborate and fanciful styles for their homes. Gone were the austere details and rigid symmetry of the Greek Revival era, and in their place builders added fancy carved details, asymmetrical rooflines, cupolas, and towers. It was a form of architectural escapism. Instead of a Greek temple, suddenly everyone wanted to live in an Italian villa or a Renaissance castle. It was the start of what we now think of as Victorian architecture.

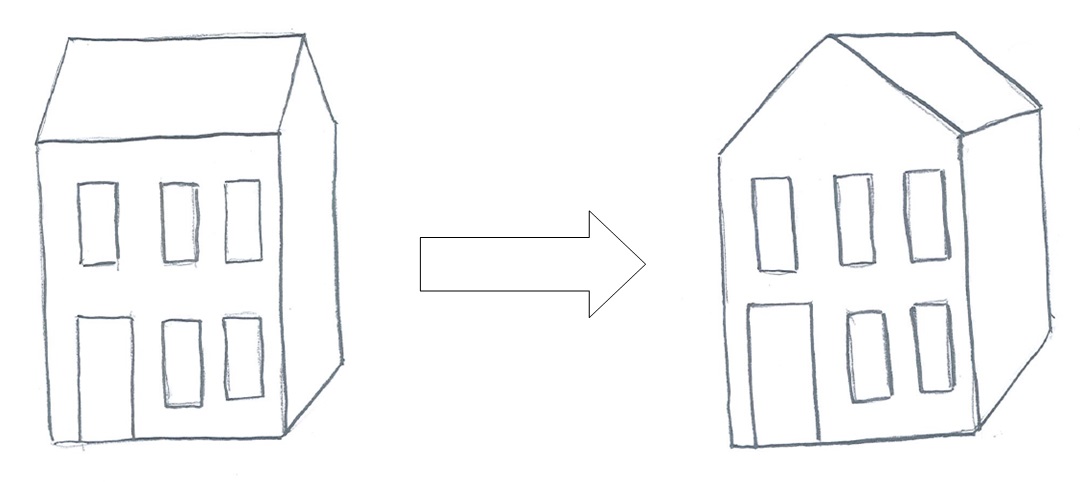

In Jeffries Point, the pace of new construction slowed in the years after the Civil War as the population of East Boston began to level off. Even so, a few dozen Victorian houses were built in the neighborhood during this time. The easiest way to identify these houses is to look at the roof. While most of Jeffries Point’s earlier Greek Revival houses have side-gabled roofs, pitched from front to back with the roof ridge running parallel to the front of the house, the neighborhood’s Victorian houses are turned 90 degrees, so that the narrow end of the house faces forward. This change looked something like this:

This reorientation, called an end house, actually originated during the Greek Revival era. Architects and builders began designing houses with the gable end facing forward because the triangular shape formed by the end of the roof allowed them to introduce decorative trim to form a pediment, the triangular roof shape found at the front of ancient Greek temples. Gable roofed end houses weren’t very popular in Jeffries Point during the Greek Revival era. There’s only one in the neighborhood, a well-preserved Greek Revival cottage dating to the 1840s.

Even after the Greek Revival style went out of fashion, end houses, with the narrow end of the house facing forward, stuck around. They were especially convenient in urban neighborhoods like Jeffries Point because they allowed builders to build long, narrow houses that fit on tightly spaced lots. Restricted by these small lots, builders in Jeffries Point in the 1870s and 80s continued building the same basic, narrow, box-shaped houses they had built during the Greek Revival era. They simply traded classically-inspired Greek Revival details for new decorative elements inspired by Italian villas and other European architecture.

In some cases, homeowners literally swapped out old, Greek Revival details for new, Victorian ones while renovating their houses. William Shattuck, a prosperous cabinetmaker, built a modest, Greek Revival house near the top of the hill in Jeffries Point sometime in the late 1840s. His house had a side-gabled roof and a flat front, and would’ve been pretty typical of middle-class Greek Revival houses built in the neighborhood at the time. But today, his house looks very different.

Shattuck’s house is the red one on the right. The gray house next door was built at about the same time, possibly by the same builder. Originally, the two houses would’ve looked almost identical. The restored facade of the house next door still features Greek Revival details, but Shattuck’s house was Victorian-ized at some point after his death in 1875. The house’s new owners undertook a major renovation to update the house, adding stylish new details.

The biggest change was the addition of a two-story, angled window bay. New house framing techniques popularized after the Civil War made it quicker and easier for builders to add angled window bays to new houses. Window bays, which flood interior rooms with light and give the illusion of extra space, became wildly popular, so much so that they’re now often considered defining features of urban, Victorian houses. Window bays even came to be seen as a mark of status – no upscale house was complete without one.

During the renovation, Shattuck’s house also lost the straight lines and hard angles of its original Greek Revival details. Instead, the new owners chose whimsical Victorian flourishes – an elaborate front porch, brackets with curlicue designs along the roofline, and curvy trim with scrolls at the base around the attic-level dormers. The end result was a fashionable home that approximated the look of the new houses that were being built in the neighborhood at the time. Today, only the house’s square footprint and side-gabled roof give away its Greek Revival past.

Very few end houses with pitched, or gable, roofs were built in Jeffries Point. Instead, in the 1870s, builders adopted a new type of roof for the neighborhood’s end houses. The mansard roof, sometimes called a French roof at the time, provided a way to create a full third floor living space while still keeping the same basic proportions of the two-story-plus-attic gable end house.

Dozens of mansard end houses were built in Jeffries Point in the 1870s and 80s. Some were single, freestanding homes, but many were semi-detached double houses, two side-by-side houses that share a central wall.

Victorian architecture is actually made up of a variety of different styles. Mansard roofed houses are associated with a style that originated in France called Second Empire. Unlike some of the other Victorian styles, which were throw backs to old, Renaissance and Medieval architecture, Second Empire buildings were considered very modern at the time. The fact that the style originated in France only made it more fashionable. Aside from mansard roofs, which were usually clad in decoratively arranged slate tiles, Second Empire houses in Jeffries Point also feature paneled window bays, decorative brackets under the eaves, and small porches or entry hoods supported by scrolled brackets over the front door.

Toward the end of the 19th century, factories began mass producing house parts. Builders and homeowners could simply look through a catalog and choose from a wide variety of affordable decorative bits to add to the front of a house. With all sorts of decorative house parts readily available, builders started adding more and more elaborate details to Jeffries Point’s houses.

This trend culminated in the fanciful architecture of the neighborhood’s triple deckers. Triple deckers are a type of three-story apartment house, with one apartment per floor, that were built in New England cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. With three apartments in a single building, triple deckers were more dense than any of the houses built before them in Jeffries Point. They were designed and built to house the neighborhood’s rapidly expanding European immigrant population. Triple deckers kept the same narrow, boxy shape and bay windows of earlier Victorian houses, but did away with pitched or mansard roofs and simply squared off the top floor and capped it with a flat roof to allow for a full, third-floor apartment.

Earlier Victorian efforts to provide housing for poor and working people were often philanthropic ventures – rich people designing and building low income housing. At the time, these rich philanthropists thought that adding decorative elements to low income housing was morally wrong, even unhealthy for the people who lived there. As a result, many of these early low income houses were incredibly plain, completely devoid of decoration. But by the time triple deckers were being built in Jeffries Point for working class immigrant families, many of the neighborhood’s builders were recent immigrants themselves. Unlike the wealthy philanthropists who proceeded them, these immigrant builders paid attention to what their customers wanted – and, unsurprisingly, it turned out that poor and working people liked living in fashionable houses just as much as rich people.

With inexpensive, factory-produced house parts readily available, these builders added a wide range of decorative elements to their triple deckers – elaborately paneled window bays, scrolled brackets under the eaves, carved garland and wreath decorations, fluted pillars to support the front porch, palladian windows. So many of these decorated triple deckers were built across Boston that people began to think of them as commonplace. But recently there’s been a revival of interest in these buildings. They’ve stood the test of time, providing affordable housing and multigenerational living arrangements to Bostonians for over a century. And with their elaborate decorative details, they deliver character in spades, making up an important part of the charm of many of Boston’s historic neighborhoods, including Jeffries Point. The city of Boston has even officially recognized their value, introducing the 3D program to provide grants, loans, and subsidies to triple decker owners to help them maintain and preserve their houses. What’s more, preserving and reusing Boston’s triple deckers is an important way to help alleviate the city’s housing shortage – in many cases, triple deckers are more dense than modern, mid-rise apartment buildings on a per-square-foot basis, offering more units of housing in the same amount of space.

At the beginning of the 20th century, as the Victorian period came to a close, Jeffries Point continued to evolve. As the neighborhood’s population continued to expand, most of the formerly single family townhouses were divided into apartments with one apartment per floor, following the triple decker model. Many of the pitched roofs on the neighborhood’s earliest Greek Revival buildings were squared off to make room for a top floor apartment. Oversized, pressed metal cornices were added along the roofline, mimicking the style of the brick tenements that were being built across Boston at the time.

By 1925, very few open lots remained in Jeffries Point. The neighborhood had taken on its present-day character, a vibrant mixture of Greek Revival and Victorian style houses, built from different materials, and modified over time to suit the needs of a changing population.

Such fun to look at all these styles! I love walking neighborhoods and picking out architectural clues. It’s really interesting that some of these Greek Revival houses were turned into “modern” Victorians. I wonder if any purists back in the day were scandalized that someone would do that to their beautiful Greek Revival house? 🙂

Haha, I wouldn’t be surprised if some long-time residents were scandalized by new owners Victorian-izing their Greek Revival House. In 1891 when the city removed a Greek-Revival-era iron fence that surrounded a nearby park, some neighbors objected. The city wrote, “the old clumsy iron fences, relics of a past age, which some old residents wished maintained, have been removed and replaced by handsomely cut curbstones.”

Then again, this particular Greek Revival House was only 30 years old when it was “modernized.” I guess it’d be like someone today altering and updating a ranch house from the late 80s? There’s a saying, ‘we hate our parents architecture, we like our grandparents architecture, and we love our great grandparents architecture.’ Maybe it held true back then as well?

Dan, I am so enjoying this series. It’s so interesting and so informative. Many thanks from this architecture and history nerd in Australia — I can’t wait to visit Boston again and look at the city through your lenses!

Thanks Anna, glad you’re enjoying it!