Old maps provide a unique window to the past. They give us an immediate sense of what a place was like when the map was drawn, and provide information about how a place has changed over time. As I’ve gotten into the research required to nominate my neighborhood for the National Register of Historic Places, I’ve found old maps of the area to be an incredibly useful resource.

There are dozens of maps of Jeffries Point spanning nearly 300 years of history in the Boston Public Library’s map collection. The earliest of these maps provide important information about the neighborhood’s origins. Many of the later maps show individual buildings in the neighborhood. By comparing the shapes and locations of buildings on historic and current maps, we can estimate construction dates, and even track additions and changes to individual buildings over time, all of which is essential information for the National Register nomination form. And these days, GIS (geographic information system) software, like QGIS, is available for free, making it easier than ever to quickly and accurately overlay and compare different maps.

But before we look at some old maps, those of you who aren’t familiar with Jeffries Point may be wondering exactly where it is. Here’s a present-day map of the area (click any of the images in this post to enlarge them).

The distinction between Jeffries Point and East Boston can be a little confusing. East Boston is one of Boston’s 23 ‘official’ neighborhoods. It’s situated along a peninsula in Boston harbor, completely separated from the rest of the city by water. It’s a big neighborhood – it covers about the same amount of land as all of Boston’s downtown neighborhoods combined – and over time, different sections of East Boston developed their own characters and identities and eventually came to be seen as distinct neighborhoods.

Jeffries Point is one of these neighborhoods-within-a-neighborhood. It’s located at the southern tip of East Boston, surrounded by the harbor on two sides. The neighborhood straddles a hill that overlooks the harbor and downtown Boston beyond. For much of its history, Jeffries Point has been defined by its harbor-front location, and even today, its harbor views, sea breezes, and maritime character continue to make it a desirable place to live.

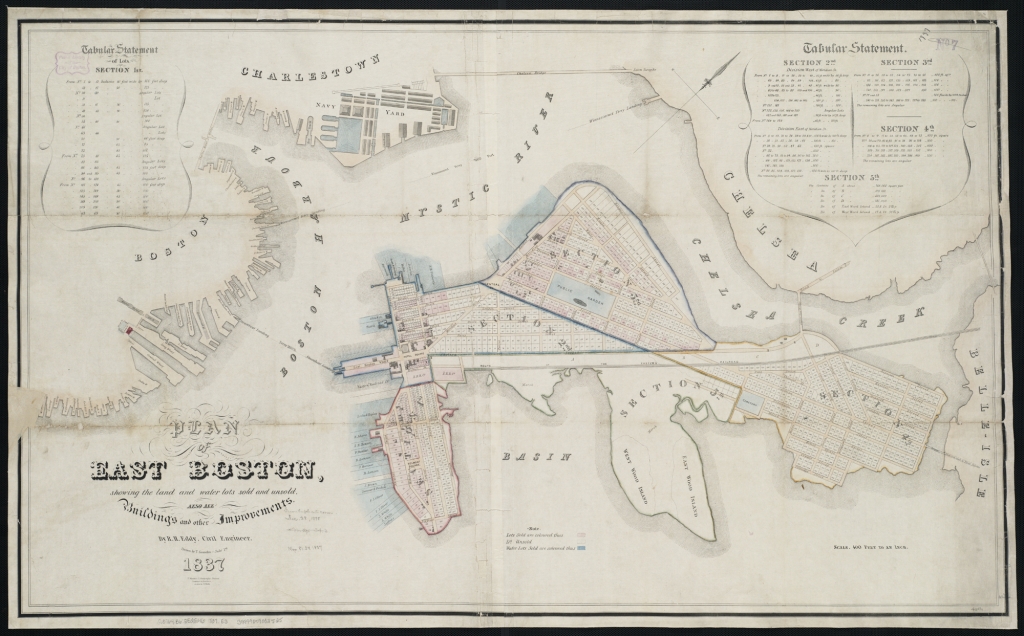

That’s Jeffries Point today. But let’s back up a bit. All the way back to 1837 when East Boston was a brand new neighborhood, located on one of the largest islands in Boston Harbor (it would be nearly 100 years before landfill projects turned East Boston into a peninsula).

A few years earlier, a group of businessmen and investors bought the island and formed a real estate venture called the East Boston Company with the goal of developing a new neighborhood. By 1837, they had laid out streets and divided the island into lots. The area we now call Jeffries Point then had the rather unimaginative name “Section 1.” Here’s a closer look at Section 1 in 1837:

A quick comparison of this map to the present-day map of Jeffries Point reveals some major differences. The landmass of the neighborhood was much smaller in 1837, and it was almost completely surrounded by water. Here’s a comparison of Jeffries Point in 1837 and Jeffries Point today. The black line is the current shoreline.

I’d never thought much about the origins of the name Jeffries Point, but the first time I saw this map, the name suddenly made sense – the neighborhood was originally a peninsula (or, more precisely, a point), and the land at the end of the point was owned by a man with the last name Jeffries. Over the years, the tidal marshes, mud flats, and shallows surrounding the neighborhood were filled in, gradually expanding the neighborhood’s landmass until it was no longer a point. In 1837, Maverick Street, along the northern edge of the neighborhood, marked the boundary between land and sea. Today, the same street divides the neighborhood from Logan Airport.

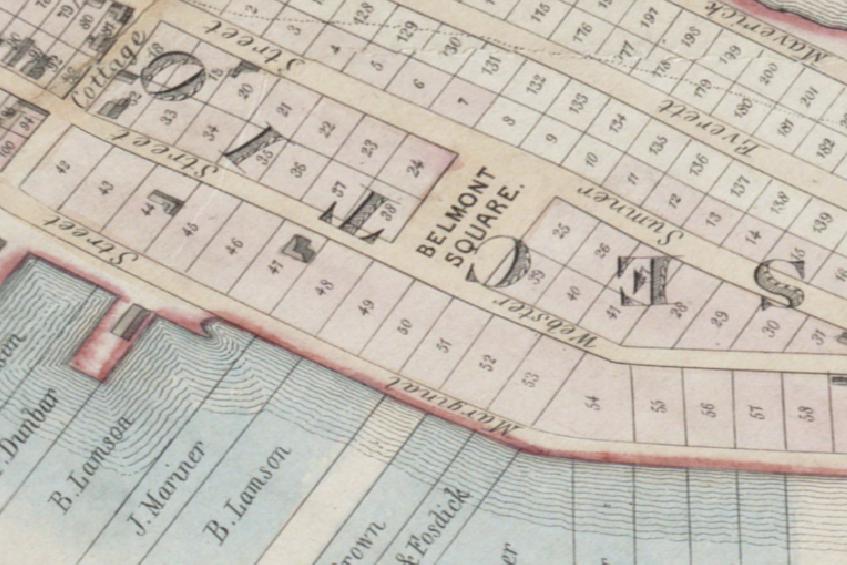

If you look closely, you’ll also find, amazingly, that many aspects of the neighborhood haven’t changed over the past 180 years. The street layout is the same. Even the street names haven’t changed. Belmont Square, a large, open space at the center of the neighborhood, still exists as well, although it’s now called Brophy Park.

At the same time, it’s important to note that this map was drawn for the East Boston Company, and it reflects the company’s aspirations, which didn’t always line up with reality. In 1837, many of the streets depicted on the map were still under construction, and the northern section of the neighborhood between Everett and Maverick Streets was a salt marsh (which helps explain why none of the lots in that area had been sold).

If a present-day resident of Jeffries Point were to travel back in time to 1837 and walk the neighborhood’s streets, she would hardly recognize her neighborhood. The area was almost completely empty. The newly graded streets cut through meadows, marshes, and pastureland. Only a handful of houses, represented by little gray rectangles on the map, had been built. The most prominent of these houses – a mansion near the top of the hill in lot 47, built for Benjamin Lamson, an early investor in the East Boston Company – would have stood out. But this mansion was demolished in 1910 to make way for an elementary school. In fact, as far as I can tell, none of the buildings shown on this map survive today.

Even though the neighborhood was sparsely settled in 1837, a close look at the size and layout of the open lots reveals clues about the East Boston Company’s vision for the neighborhood. In fact, this was a time before zoning codes existed, and decisions about lot size and layout were one of the only ways the East Boston Company could influence the course of development in the neighborhood. The smallest lots in Jeffries Point were located at the western edge of the neighborhood, with larger lots further east and the largest lots located along the southern waterfront.

The reason for the varied lot sizes has to do with the scarcity of transportation options in the 1830s. Public transportation was nearly non-existent, and private transportation was largely limited to horses, which were unavailable to all but the wealthiest city dwellers. In their day-to-day lives, most people walked wherever they needed to go. Today, walkable neighborhoods are desirable, but in the 1830s they were essential. Factories, docks, shops, churches, schools, worker housing, and housing for wealthy business owners all needed to be within easy walking distance of one another. It was this kind of intensely walkable, mixed-use neighborhood that the East Boston Company had in mind when they laid out East Boston over 180 years ago.

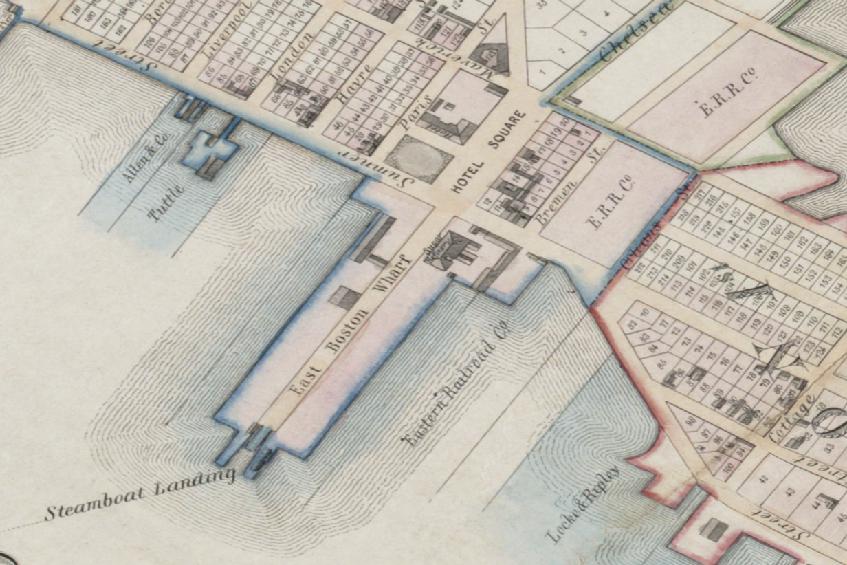

Steam-powered ferries, a relatively new technology in the 1830s, provided a vital link between East Boston and downtown. Without this fast and reliable form of water transportation, East Boston likely would’ve remained farmland. So it’s no surprise that the neighborhood’s earliest development was clustered around the ferry landing, just to the west of Jeffries Point near Maverick Square (then known as Hotel Square).

By 1837 a sugar refinery, warehouses, and a hotel had been built in this area. The deep, narrow lots surrounding Maverick Square, including the lots in the western end of Jeffries Point, were mostly empty. But these small lots were sized to encourage dense development around the ferry landing, then the neighborhood’s industrial and commercial hub. In particular, these small, affordable lots were designed to accommodate rows of modest worker housing to support East Boston’s burgeoning industrial economy.

Just a quarter-mile to the east, the lots became much larger. With their hilltop location, harbor views, and proximity to the landscaped Belmont Square, these lots were set aside for the new neighborhood’s wealthiest residents. At upwards of three times the size of the lots surrounding Maverick Square, these lots were large enough to accommodate grand houses, stables, and landscaped grounds. Benjamin Lamson’s mansion in lot 47 provided an early prototype for this kind of upscale development. Despite the intended grandeur of these lots, they were located right next to higher density worker housing, within easy walking distance of the ferry landing and the neighborhood’s industrializing waterfront.

Decisions made about Jeffries Point’s layout in the 1830s have reverberated through the years, and in many ways still define the neighborhood I live in today. Constrained by the limits of the transportation technology available at the time, the East Boston Company designed a neighborhood where businesses, housing, factories, and docks were built side by side. The end result was a vibrant, 19th century urban neighborhood. But this dense, walkable layout has remained vital today for an entirely different set of reasons. It’s environmentally sustainable, making walking, biking, and using public transit more attractive than driving a car; it allows residents to live close to work and reduces commute times; its density and human scale encourage a tight knit community where neighbors know one another; and it produced an architecturally diverse neighborhood that now supports a diverse community with a variety of housing options, from grand townhouses to modest workers’ cottages, converted factory lofts to apartment houses.

The original planners of East Boston never could have imagined that their design for the neighborhood would remain relevant 180 years later, but the dense, multi-use development that they encouraged may be their greatest legacy.

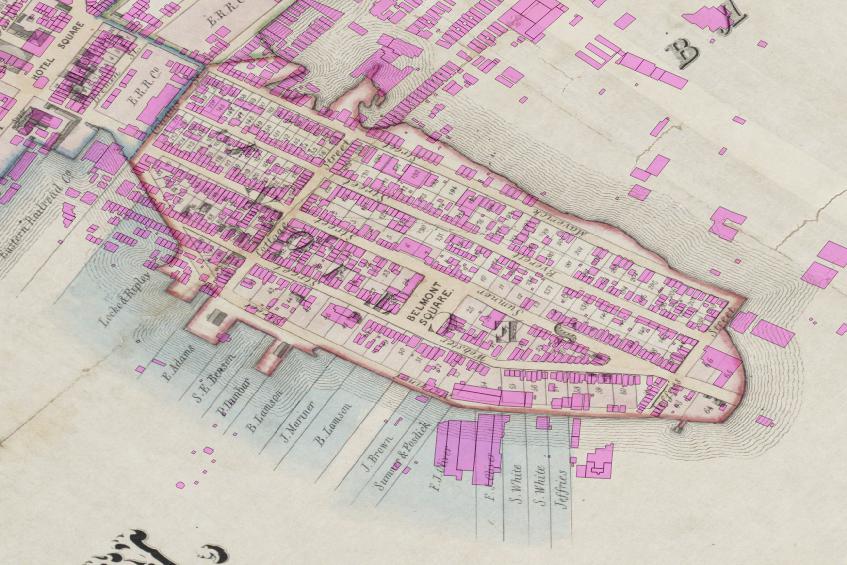

I’ll leave you with a map showing present-day buildings (in pink) overlaid on the 1837 map of Jeffries Point.

How did we get from the nearly empty Jeffries Point of the 1830s to the dense, urban neighborhood we see today? Check back next time for Part 2 to find out.

This post is part of a series about the process of nominating my neighborhood for the National Register of Historic Places. To see all of the posts in the series, click here.

This is fascinating! I passed your post to my husband. How did you get the map images? Has the library digitized them?

Yes! We’re lucky that the library has digitized most of their extensive map collection. They have historic maps from all over the world, not just Boston. You can browse the collection here: The Leventhal Map Center

Thank you. This is very interesting.

Thanks! There are more posts on Jeffries Point’s history to come, I hope you’ll keep following along!

Thanks so much for putting this all together! Seriously helping with some coursework on Transit-Oriented Development, and also further vindicating my interest in Jeffries Point.

John Jeffries Jr build a cabin on the tip of Noddle’s Island in the early 1830s that came to be known as Jeffries point. He founded the mass eye and ear. His father took the first balloon flight in Europe over the English Channel. By the way, Maverick is Samuel Maverick who once owned Noddles Island around 1628, one of his descendants moved to Texas and was a rancher but not a good one and didnt brand his horses so they were known as Maverick’s which gave us the term maverick, unbranded.